London – 16 January 2017

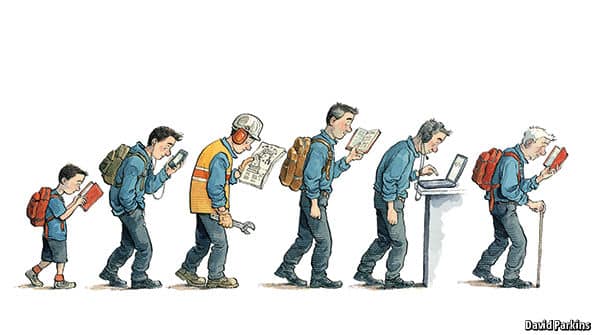

Technology often ends up creating more jobs than it destroys, but it unquestionably forces change on huge numbers of people. Manufacturing offers fewer metal-bashing jobs than it once did. The share of the American workforce employed in routine office jobs declined from over 25% to 21% between 1996 and 2015. New skills, such as the ability to code, are in heavy demand. In response, policymakers and companies tout the need for the next big revolution in education. This one goes by the name of “lifelong learning”. If people are to stay employable and move from declining occupations to emergent ones, they must be able to acquire new skills throughout their careers.

This week The Economist publishes a special report on lifelong learning, written by Andrew Palmer, the paper’s business affairs editor.

- Highlights:

A new ecosystem for skills provision is emerging. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) like Coursera and Udacity, which were feted at the start of the decade and then dismissed as hype within a couple of years, have developed new employment-focused business models. LinkedIn, a professional networking site, is offering online training courses. Amazon’s cloud-computing division also has an education offering. - Universities are offering cheaper, more accessible and more modular content. When Georgia Tech decided to offer an online version of its masters in computer science at low cost, it seemed to risk cannibalisation of its campus degree, but the two sorts of courses turned out to attract quite different age groups.

- Companies are putting increasing emphasis on employees’ ability and willingness to keep learning. Infosys talks about “learning velocity”—the process of going from a question to a good idea in a matter of days or weeks. Microsoft makes learning part of its appraisal process. AT&T and UTC both offer generous tuition reimbursement schemes for their employees.

- The relationship between ageing and cognition is complicated. People’s performance on vocabulary and general-knowledge tests keeps improving until their 70s, but their ability to grapple with new problems declines from an early age.

- The emergent market for lifelong learning is a good thing–but mainly for those who are privileged already. About 80% of the students on Coursera have at least one degree under their belt. A radical approach is needed to ensure that lower-skilled workers too have opportunities to go on learning. Singapore offers a model. Every Singaporean above the age of 25 is given a credit that can be used to pay for training courses run by approved providers, topped up by generous subsidies for those aged 40 and over.

Link to report: http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21714341-it-easy-say-people-need-keep-learning-throughout-their-careers-practicalities